Here Lies

By H. W. GUERNSEY

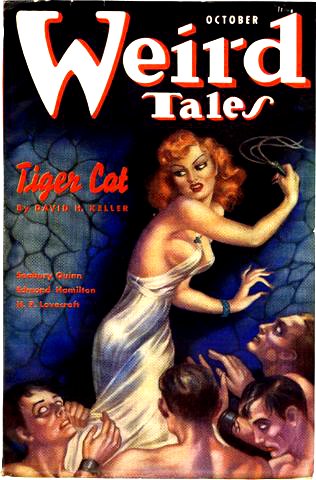

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from Weird Tales October1937. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S.copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Chauncey knocked the dottle out of his corncob and briefly startled OldShep by inquiring unemotionally, "Will you never finish that blastedstick?"

Which in Old Chauncey was tantamount to fury. Words being preciousthings, both old boys hoarded every syllable; Shep tightened hisleathery lips and with the scalpel-point of the knife flicked away amote of pine. Each link of the chain he was whittling from thatinterminable stick of soft pine resembled ivory in its satin finish. Hemight produce one link in a day or let it require a full week. No hurry.The current chain numbered four hundred and seventy-two links. Amasterpiece.

Under Shep's surreptitious scrutiny, Old Chauncey stood erectpurposefully and stalked to the woodpile. There a fat log stood on end.With one swift, seemingly effortless stroke of the ax he cleft the login two, spat explosively and hiked into the house wagging his jaw.

The log-built house, a jewel of conscientious carpentry, stood on thewooded elevation called St. Paul's Hill, near town. On the side hill onehundred and twenty feet below stood another log-built affair, formerlythe ice-house. Since Old Shep had become Chauncey's permanent guest,this structure had been equipped with furnishings as complete andcomfortable as the house, including plumbing. So there was no reason forShep to hang around Old Chauncey's kitchen.

The housekeeper, Celia Lilleoden, performed the chores incidental toboth houses with such easy efficiency that old Chauncey was repeatedlyreminded of his bachelorhood. From continually sunning themselves behindthe kitchen like two old snakes the men had acquired a wrinkledblack-walnut finish, but Celia still retained the firm, buxom ripenessof an apple.

As a practical communist Old Chauncey kept his latch-key out byinclination. His generosity was limitless.

Thus, Old Shep did not have to ask for anything he wanted. It was shareand share alike.

For example, he charged tobacco to Old Chauncey's account at the storein town. He always had. If he preferred a grade of tobacco superior towhat Old Chauncey himself used, such was his privilege. A plug is aplug.

Shep and Chauncey once had occupied the same double desk of rawcherrywood in the schoolhouse which was now a weedy hill of rubble androtten wood a half-mile out on the backroad.

Besides words, Old Shep hoarded tobacco plugs in case the cause ofcommunism ever collapsed.

In accordance with this scheme of living, Old Chauncey gradually becameaccustomed to being spared the nuisance of opening the occasional letterhe received from another old soldier in Sackett's Harbor, New York. Atfirst Shep had gone to the trouble of sneaking the mail down to theice-house and steaming it open. But currently the mail arrived slit openwithout any subterfuge. The knife, incidentally, was the better of OldChauncey's two. Shep had borrowed it, knowing that in communism therecan be no Indian giving.

On one occasion Chauncey accosted Old Shep behind the kitchen with acrumpled letter in his fingers.

"Shep," he suggested casually, "I wish you'd slit my letters open at thetop instead of an end. It wouldn't bunch the writing up so much when youshove it back inside."

"Chauncey," Old Shep replied trembling