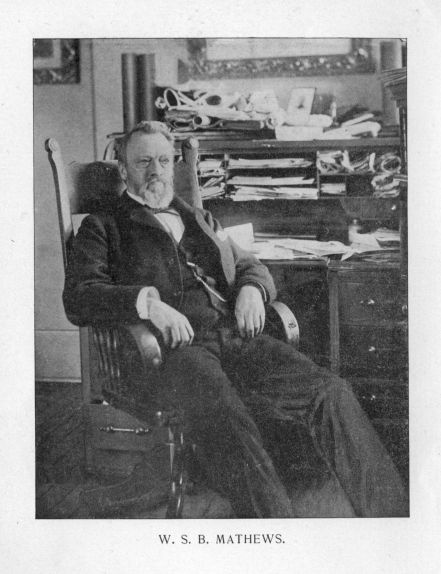

W. S. B. MATHEWS.

THE

MASTERS AND THEIR MUSIC

A SERIES OF ILLUSTRATIVE PROGRAMS, WITH

BIOGRAPHICAL, ESTHETICAL, AND

CRITICAL ANNOTATIONS

DESIGNED AS AN INTRODUCTION TO

MUSIC AS LITERATURE

FOR THE USE OF CLUBS, CLASSES, AND

PRIVATE STUDY

BY

W. S. B. MATHEWS

Author of "How to Understand Music," "A Popular History of Music,"

"Music: Its Ideals and Methods," "Studies in Phrasing,"

"Standard Grades," Etc., Etc.

Philadelphia

Theodore Presser

1708 Chestnut Str.

COPYRIGHT, 1898, BY THEO. PRESSER

PREFACE.

When a musical student begins to think of music as a literature and toinquire about individualities of style and musical expression, it isnecessary for him to come as soon as possible to the fountainheads ofthis literature in the works of a few great masters who have set thepace and established the limits for all the rest. In the line ofpurely instrumental music this has been done by Bach, Haydn, Mozart,Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Chopin, Liszt, and Wagner. Thelatter, who exercised a vast influence upon the manner of developing amusical thought and in the selection of the orchestral colors in whichit can be expressed advantageously, powerfully stimulated all composerslater than himself, nevertheless exerted this influence at second-hand,so to say, never having written purely instrumental movements, butmerely dramatic accompaniments of one intensity or another. Hence, forour present purposes we may leave Wagner out altogether. Practically,down to about the year 1875, everything in instrumental music isoriginal with the masters already mentioned, or was derived from themor suggested by them. Hence, in order to understand instrumental musicwe have, first of all, to make a beginning with the peculiarities,individualities, beauty, and mastership of these great writers. Suchis the design of the following programs and explanatory matter.

My first intention has been to provide for the regular study of amusical club, in which the playing is to be contributed by activemembers designated in advance, the accessory explanations to be readfrom these pages. I have thought that the playing might be dividedbetween several members, through which means the labor for each wouldbe reduced, and, on the whole, an intimate familiarity with the musicbe more widely extended in the club. This method will have thedisadvantage of leaving a part of every program less well interpretedthan the others, whereby it will sometimes happen that valuable partswill not be properly appreciated. The advantages of this method