Star, Bright

By MARK CLIFTON

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction July 1952.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

There is no past or future, the children said;

it all just is! They had every reason to know!

Friday—June 11th

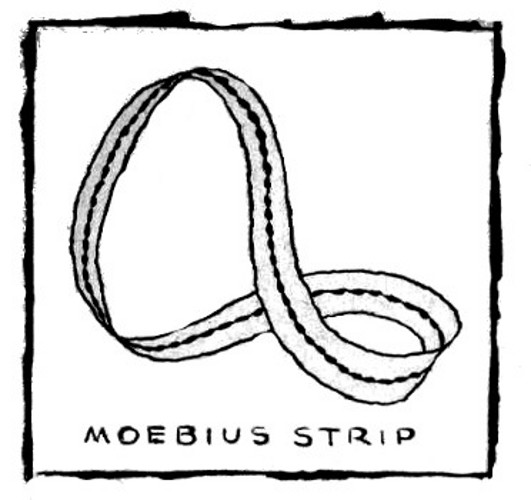

At three years of age, a little girl shouldn't have enough functioningintelligence to cut out and paste together a Moebius Strip.

Or, if she did it by accident, she surely shouldn't have enoughreasoning ability to pick up one of her crayons and carefully trace thecontinuous line to prove it has only one surface.

And if by some strange coincidence she did, and it was still just anaccident, how can I account for this generally active daughter ofmine—and I do mean active—sitting for a solid half hour with herchin cupped in her hand, staring off into space, thinking with suchconcentration that it was almost painful to watch?

I was in my reading chair, going over some work. Star was sitting onthe floor, in the circle of my light, with her blunt-nosed scissors andher scraps of paper.

Her long silence made me glance down at her as she was taping the twoends of the paper together. At that point I thought it was an accidentthat she had given a half twist to the paper strip before joining thecircle. I smiled to myself as she picked it up in her chubby fingers.

"A little child forms the enigma of the ages," I mused.

But instead of throwing the strip aside, or tearing it apart as anyother child would do, she carefully turned it over and around—studyingit from all sides.

Then she picked up one of her crayons and began tracing the line. Shedid it as though she were substantiating a conclusion already reached!

It was a bitter confirmation for me. I had been refusing to face itfor a long time, but I could ignore it no longer.

Star was a High I.Q.

For half an hour I watched her while she sat on the floor, one kneebent under her, her chin in her hand, unmoving. Her eyes were wide withwonderment, looking into the potentialities of the phenomenon she hadfound.

It has been a tough struggle, taking care of her since my wife's death.Now this added problem. If only she could have been normally dull, likeother children!

I made up my mind while I watched her. If a child is afflicted, thenlet's face it, she's afflicted. A parent must teach her to compensate.At least she could be prepared for the bitterness I'd known. She couldlearn early to take it in stride.

I could use the measurements available, get the degree of intelligence,and in that way grasp the extent of my problem. A twenty point jumpin I.Q. creates an entirely different set of problems. The 140 childlives in a world nothing at all like that of the 100 child, and a worldwhich the 120 child can but vaguely sense. The problems which vex andchallenge the 160 pass over the 140 as a bird flies over a field mouse.I must not make the mistake of posing the problems of one if she is theother. I must know. In the meantime, I must treat it casually.

"That's called the Moebius Strip, Star," I interrupted her thoughts.

She came out of her reverie with a start. I didn't like the