Infinity's Child

By Charles V. DeVet

"You must kill Koski," the leader said.

"But I'll be dead before I get there," Buckmaster replied.

"What's that got to do with it?" the leader wanted to know.

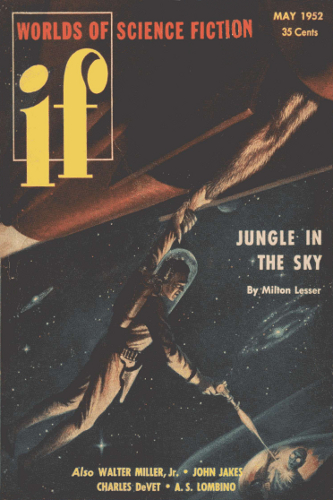

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, May 1952.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The sense of taste was always first to go. For a week Buckmaster hadignored the fact that everything he ate tasted like flavorless gruel.He tried to make himself believe that it was some minor disorder ofhis glandular system. But the eighth day his second sense—that offeeling—left him and he staggered to his telephone in blind panic.There was no doubt now but that he had the dread Plague. He was gladhe had taken the precaution of isolating himself from his family. Heknew there was no hope for him now.

They sent the black wagon for him.

In the hospital he found himself herded with several hundred othersinto a ward designed to hold less than a hundred. The beds were crowdedtogether and he could have reached to either side of him and touchedanother ravaged victim of the Plague.

Next to go would be his sense of sight. Hope was a dead thing withinhim. Even to think of hoping made him realize how futile it would be.

He screamed when the walls of darkness began to close in around him. Itwas the middle of the afternoon and a shaft of sunlight fell across thegrimy blankets on his bed. The sunlight paled, then darkened and wasgone. He screamed again. And again.

He heard them move him to the death ward then, but he could not evenfeel their hands upon him.

Three days later his tongue refused to form words. He fought a namelessterror as he strove with all the power of his will to speak. If hecould say only one word, he felt, the encroaching disease would have toretreat and he would be safe. But the one word would not come.

Four horrible days later the sounds around him—the screams and themuttering—became fainter, and he faced the beginning of the end.

At last it was all over. He knew he was still alive because he thought.But that was all. He could not see, hear, speak, feel, or taste.Nothing was left except thought; stark, terrible, useless thought!

Strangely the awful horror faded then and his mind experienced agrateful release. At first he suspected the outlet of his emotions hadsomehow become atrophied as had his senses, and that he was peacefulonly because his real feelings could not break through the numbness.

However, some subtle compulsion within him—some power struggling inits birth-throes—was beginning to breed its own energy and he sensedthat it was the strength of that compulsion that had subdued the terror.

He was at peace now, as he had never been at peace before. For atime, he did not question—was entirely content to lie there andsavor the wonderful feeling. He had lost even the definition of fear.No terror now from the slow closing of the five doors; no regrets;no forebodings. Only a vast happiness as he seemingly viewed life,suffering, and death as a man standing on a cliff looking out over agreat misty valley.

But soon came wonder and analysis. He looked backward and thought:It was a world, but not my world. These are memories but not mymemories. I lived them and knew them—yet none of them belongs to me.Strange—this soul-fiber with which I think—the last function left tome—is not a soul-fiber I have ever known before.