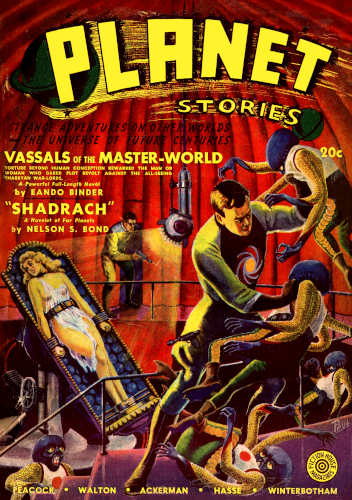

DEAD MAN'S PLANET

By R. R. WINTERBOTHAM

For unmarked ages a dead man kept his ghostly

vigil on that barren, frozen asteroid.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Fall 1941.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

"A life-saver!" Mick said, bringing the space freighter down with agentle bump on the huge, shapeless mass of rock and iron that floatedbetween Mars and Jupiter.

The term huge was purely relative, for the asteroid was scarcely tenmiles in diameter at its thickest point, and its axis could not havebeen more than twelve miles long.

Mick switched off the rockets, opened a locker and pulled forth a suitof heavy, furlined, airtight garments which he slipped over his uniform.

The communication speaker buzzed.

"Hey, Mick! Are you still on the bridge?"

Alf Rankin was calling from the charting room.

"Yes, Alf. What's the trouble." Mick Conner was sealing his space suit.

"This isn't an ordinary asteroid, Mick. It isn't barren. There's stuffgrowing on it."

"That's nothing to get goggle-eyed about, Alf. There's moss on Eroswhich is smaller than this. And there are 142 different kinds of plantsand one intermediate—animal-vegetable—organism on Juno."

"Hm-m!"

Of course this was a surprise to Alf, who had never made a landing onthe asteroids before. Science had rather neglected the asteroids duringthe rapid development of interplanetary flight, yet there were manyinteresting sights to be seen on the 4,000 minor planets that floatedbetween Jupiter and Mars.

"Get on your space togs and oxygen helmet and we'll fix that brokenjet," Mick said. "We'll be ready to go in three hours."

Mick sealed his helmet and stepped into the automatic lock leading fromthe control bridge to the roof of the streamlined rocket.

He held tightly to the rail of the observation platform, knowing thatthe gravity of this nameless planet was next to zero. A man might jumpone thousand feet into the sky without exertion and, if he wasn'tcareful, he might fling himself so high that he would be unable toland—he might become a satellite of this grain of cosmic dust.

Mick hooked the lifeline from his belt to the rail of the platform andstepped over the side. Instead of falling, he floated a few inches asecond downward to the ground. In gravity like this a man might jumpoff Mt. Everest—if there were an Everest—and land without injury.

Alf, the square-jawed giant who manned the engines of the rocket ship,emerged from the lower locks and fastened his lifeline to the ironladder extending to the ground.

"Look at that stuff, Mick," Alf spoke into his radio telephone. Hepointed to a dense growth, barely visible in Jupiter's light, justnorth of the ship. "It looks like corn. Good old American maize!"

Mick who had been examining the damaged portion of the starboardrockets, glanced in the direction Alf was pointing. In even, nicelycultivated rows, stood tasseled stalks.

"You don't suppose this place is inhabited by men!" Alf's voice wasawed.

"It can't be. There's no air," Mick replied. "Anyhow, it isn't corn. Itmust be something else. You know there are doubles all over the system.The Martian pumpkins aren't even vegetables, but they're a species ofmollusk. Even if this is corn, it's different, because corn depends oncarbon dioxide in the atmosphere."

"Maybe there's carbon dioxide in the rocks."

"Then this wouldn't be like terrestrial maiz