MIRACLE BY PRICE

BY IRVING E. COX, JR.

They said old Doctor Price was an inventive

genius but no miracle worker. Yet—if he didn't

work miracles in behalf of an over-worked

little guy named Cupid, what was he doing?

Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

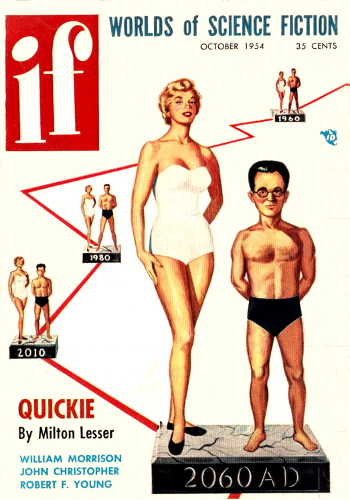

Worlds of If Science Fiction, October 1954.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Memo to: Clayton, Croyden and Hammerstead, Attorneys

Attention: William Clayton

From: Walter Gordon

Dear Bill:

Enclosed is the itemized inventory of the furnishings of the late Dr.Edward Price's estate. As you requested, I personally examined thelaboratory. Candidly, Bill, you needed a psychiatrist for the job, nota graduate physicist. Dr. Price was undoubtedly an inventive genius adecade ago when he was still active in General Electronics, but his labwas an embarrassing example of senile clutter.

You had an idea, Bill, that before he died Price might have beenplaying around with a new invention which the estate could develop andpatent. I found a score of gadgets in the lab, none of them finishedand none of them built for any functional purpose that I could discover.

Only two seemed to be completed. One resembled a small, portable radio.It was a plastic case with two knobs and a two-inch speaker grid. Therewas no cord outlet. The machine may have been powered by batteries, forI heard a faint humming when I turned the knobs. Nothing else. Dr.Price had left a handwritten card on the box. He intended to call ita Semantic-Translator, but he had noted that the word combination wasawkward for commercial exploitation, and I suppose he held up a patentapplication until he could think of a catchier name. One sentence onthat card would have amused you, Bill. Price wrote, "Should wholesalefor about three-fifty per unit." Even in his dotage, he had an eye forprofit.

The Semantic-Translator—whatever that may mean—might have hadpossibilities. I fully intended to take it back with me to GeneralElectronics and examine it thoroughly.

The second device, which Price had labeled a Transpositor, was largeand rather fragile. It was a hollow cylinder of very small wires,perhaps a foot in diameter, fastened to an open-faced console crowdedwith a weird conglomeration of vacuum tubes, telescopic lenses andmirrors. The cylinder of wires was so delicate that the motion of mybody in the laboratory caused it to quiver. Standing in front of thewire coil were two brass rods. A kind of shovel-like chute was fixed toone rod (Price called it the shipping board). Attached to the secondrod was a long-handled pair of tongs which he called the grapple.

The Transpositor was, I think, an outgrowth of Price's investigationof the relationship between light and matter. You may recall, Bill,the brilliant technical papers he wrote on that subject when he wasstill working in the laboratories of General Electronics. At the timePrice was considered something of a pioneer. He believed that light andmatter were different forms of the same basic element; he said thateventually science would learn how to change one into the other.

I seriously believe that the Transpositor was meant to do preciselythat. In other words, Price had expected to transpose the atomicstructure of solid matter into light, and later to reconstruct theoriginal matter again. Now don't assume, Bill, tha