The Impossible Voyage Home

By F. L. WALLACE

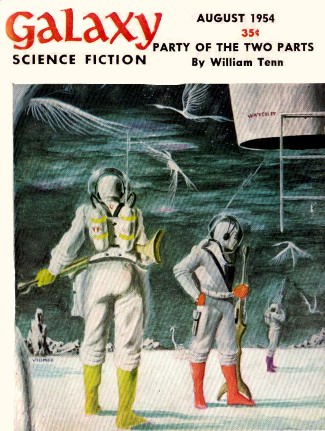

Illustrated by DICK FRANCIS

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from Galaxy Science FictionAugust 1954. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that theU.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

"Space life expectancy has been increased to twenty-five months and sixdays," said Marlowe, the training director. "That's a gain of a fullmonth."

Millions of miles from Earth, Ethan also looked discontentedly proud."A mighty healthy-looking boy," he declared.

Demarest bent a paperweight ship until it snapped. "It's something.You're gaining on the heredity block. What's the chief factor?"

"Anti-radiation clothing. We just can't make them effective enough."

Across space, on distant Mars, Amantha reached for the picture. "Howcan you tell he ain't sickly? You can't see without glasses."

Ethan reared up. "Jimmy's boy, ain't he? Our kids were always healthy,'specially the youngest. Stands to reason their kids will be better."

"Now you're thinking with your forgettery. They were all sick, one timeor another. It was me who took care of them, though. You always couldfind ways of getting out of it." Amantha touched the chair switch.

The planets whirled around the Sun. Earth crept ahead of Mars, Venusgained on Earth. The flow of ships slackened or spurted forth anew,according to what destination could be reached at the moment:

"A month helps," said Demarest. "But where does it end? You can'tenclose a man completely, and even if you do, there still is the air hebreathes and food he eats. Radiation in space contaminates everythingthe body needs. And part of the radioactivity finds its way to thereproductive system."

Marlowe didn't need to glance at the charts; the curve was beginningto flatten. Mathematically, it was determinable when it wouldn't rise atall. According to analysis, Man someday might be able to endure theradiation encountered in space as long as three years, if exposure timeswere spaced at intervals.

But that was in the future.

"There's a lot you could do," he told Demarest. "Shield the atomics."

"Working on it," commented Demarest. "But every ounce we add cuts downon the payload. The best way is to get the ship from one place toanother faster. It's time in space that hurts. Less exposure time, moretrips before the crew has to retire. It adds up to the same thing."

On Mars, Amantha fondled the picture. "Pretty. But it ain't real." Shelaid it aside.

Ethan squinted at it. "I could make you think it was. Get it enlarged,solidified. Have them make it soft, big as a baby. You could hold it inyour lap."

"Outgrew playthings years ago." Amantha adjusted the chair switch, butthe rocking motion was no comfort.

Ethan turned the picture over, face down. "Nope. Hate to back you up,'Mantha, but it ain't the same. There's nothing like a baby, wettin' andsquallin' and smilin', stubborn when it oughtn't to be and sweet andgentle when you don't expect it. Robo-dolls don't fool anybody who'sever held the real thing."

In the interval, Earth had drawn ahead. The gap between the two planetswas widening.

"That'