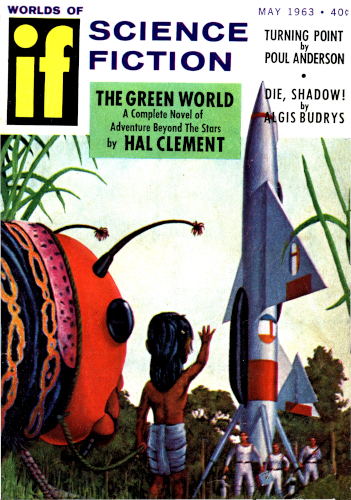

THE GREEN WORLD

BY HAL CLEMENT

The planet was an enigma—and

its solution was death!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, May 1963.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

I

A zoo can be a rather depressing place, or it can be a lot of fun, orit can be so dull as to make the mind wander elsewhere in self-defense.In fairness to Emeraude, Robin Lampert had to concede that this one wasnot quite in the last group. He had been able to keep his attention onthe exhibits. This was, in a way, surprising; for while a frontier townhas a perfect right to construct and maintain a zoo if it wishes, onecan hardly expect such a place to do a very good job.

The present example was, it must be admitted, not too good. Theexhibits were in fairly ordinary cages—barred for the largercreatures, glassed for the smaller ones. No particular attempt had beenmade to imitate natural surroundings. The place looked as artificial asbare concrete and iron could make it. To a person used to the luxuriesprovided their captive animals by the great cities of Earth and hersister planets, the environment might have been a gloomy one.

Lampert did not feel that way. He had no particular standards of whata zoo should be, and he would probably have considered attempts atreproduction of natural habitat a distracting waste of time. He was nota biologist, and had only one reason for visiting the Emeraude zoo; theguide had insisted upon it.

There was, of course, some justice in the demand. A man who was takingon the responsibility of caring for Lampert and his friends in thejungles of Viridis had a right to require that his charges know whatthey were facing. Lampert wanted to know, himself; so he had readconscientiously every placard on every cage he had been able to find.These had not been particularly informative, except in one or twocases. Most of the facts had been obvious from a look at the cages'inhabitants. Even a geophysicist could tell that the Felodon, forexample, was carnivorous—after one of the creatures had bared a ratherstartling set of fangs by yawning in his face. The placard had toldlittle more. Less, in fact, than McLaughlin had already said about thebeasts.

On the other hand, it had been distinctly informative to read that asmall, salamanderlike thing in one of the glass-fronted cages was aspoisonous as the most dangerous of Terrestrial snakes. There had beennothing in its appearance to betray the fact. It was at this point,in fact, that Lampert began really to awaken to what he was doing.

He was aroused all the way by McLaughlin's explanation of a numberwhich appeared on a good many of the placards. Lampert had noticedit already. The number was always, it seemed, different, thoughalways in the same place, and bore signs of much repainting. It boreno relationship to any classification scheme that Lampert knew, andneither of the paleontologists could enlighten him. Eventually heturned to McLaughlin and asked—not expecting a useful answer, sincethe man was a guide rather than a naturalist. However, the tall mangave a faint smile and replied without hesitation.

"That's just the number of human deaths known to have been caused bythat animal this year." It did not comfort Lampert too greatly to learnthat the year used was that of Viridis, some seventeen times as long asthat of Earth. For the Felodon the number stood at twelve. This w