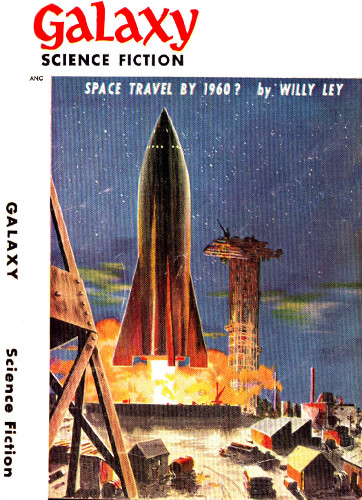

THE MOONS OF MARS

By DEAN EVANS

Illustrated by WILLER

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction September 1952.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Every boy should be able to whistle, except,

of course, Martians. But this one did!

He seemed a very little boy to be carrying so large a butterfly net. Heswung it in his chubby right fist as he walked, and at first glance youcouldn't be sure if he were carrying it, or it carrying him.

He came whistling. All little boys whistle. To little boys, whistlingis as natural as breathing. However, there was something peculiar aboutthis particular little boy's whistling. Or, rather, there were twothings peculiar, but each was related to the other.

The first was that he was a Martian little boy. You could be very sureof that, for Earth little boys have earlobes while Martian little boysdo not—and he most certainly didn't.

The second was the tune he whistled—a somehow familiar tune, but onewhich I should have thought not very appealing to a little boy.

"Hi, there," I said when he came near enough. "What's that you'rewhistling?"

He stopped whistling and he stopped walking, both at the same time, asthough he had pulled a switch or turned a tap that shut them off. Thenhe lifted his little head and stared up into my eyes.

"'The Calm'," he said in a sober, little-boy voice.

"The what?" I asked.

"From the William Tell Overture," he explained, still looking up at me.He said it deadpan, and his wide brown eyes never once batted.

"Oh," I said. "And where did you learn that?"

"My mother taught me."

I blinked at him. He didn't blink back. His round little face stillheld no expression, but if it had, I knew it would have matched thetitle of the tune he whistled.

"You whistle very well," I told him.

That pleased him. His eyes lit up and an almost-smile flirted with thecorners of his small mouth.

He nodded grave agreement.

"Been after butterflies, I see. I'll bet you didn't get any. This isthe wrong season."

The light in his eyes snapped off. "Well, good-by," he said abruptlyand very relevantly.

"Good-by," I said.

His whistling and his walking started up again in the same spot wherethey had left off. I mean the note he resumed on was the note whichfollowed the one interrupted; and the step he took was with the leftfoot, which was the one he would have used if I hadn't stopped him.I followed him with my eyes. An unusual little boy. A most preciselymechanical little boy.

When he was almost out of sight, I took off after him, wondering.

The house he went into was over in that crumbling section which formsa curving boundary line, marking the limits of those frantic and uglyoriginal mine-workings made many years ago by the early colonists. Itseems that someone had told someone who had told someone else thathere, a mere twenty feet beneath the surface, was a vein as wide asa house and as long as a fisherman's alibi, of pure—pure, mindyou—gold.

Back in those days, to be a colonist meant to be a rugged individual.And to be a rugged individual meant to not give a damn one way oranother. And to not give a damn one way or another meant to make onehell of a mess on the placid face of Mars.

There had not been any gold found, of course, and now, for the mostpart, the mining shacks so hastily t