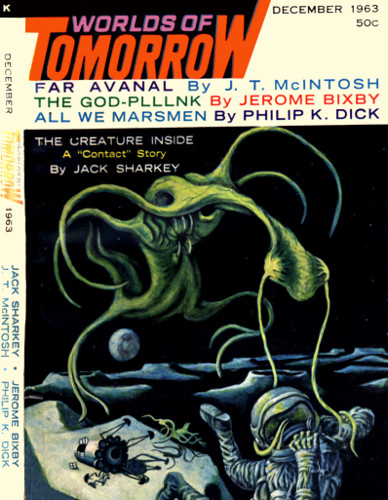

THE TROUBLE WITH TRUTH

BY JULIAN F. GROW

ILLUSTRATED BY LUTJENS

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of Tomorrow December 1963

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Nobody knows where it will end. I only know where

it began—in Rutlan—twenty-four hours ago!

I

"The WPA stinks," Sara said. Now, I've known Sara four year. We've beenengaged three times and married once—only marriage, not matrimony—soI pretty much know what to expect from her. I didn't speak.

She rummaged in her belt pouch and waved something from it under mynose. It was a plastic tube, pointed and dark at one end. "Do you knowwhat this is?" She said it loud enough to make people at other tableslook away from the program on the Rutlan Community Room cubeo.

As it happened, I did know what it was. "Sure," I said. "It's a pencil."

"A pencil!" she hissed back. "A pencil such as they've been makingfor, I don't know, maybe three hundred years. Plastic and a blackcore, that's all. An atavistic, human writing instrument. But there ismore real, solid news in this one pencil than in all the gadgets andwires and whirling wheels of the whole stinking WPA, your World PressAssociation! And in one edition of my poor little Argus, that funnylittle country monthly...."

Fortunately, at this point, the familiar Thomas Edison Pageantbroadcast ended and the announcer on the cubeo rang his Town Crierbell. Copies of the Northeast Region edition of the Sun began pouringout of the Fotofax slot. As a matter of habit I rose and got a Sunfor each of us, Sara taking hers with a snort, and sat down again asthe announcer gave the World Press Association opening format:

"An informed people is a free people," he droned. "Read your Sun andknow the truth. Stand by now for an official synopsis of the day'shappenings prepared by the World Press Association."

We both got up to go, leaving our Suns behind as most in the roomlater would too. "Oh, I almost forgot," Sara said, the way she doeswhen she's been thinking about something all day. "That reminds me. I'mpregnant."

"Ah?" I said. "Okay. Good." Not just marriage this time: matrimony itwas. We walked out, and she held my hand, a thing she doesn't normallydo.

On the belt-way to Milbry and Sara's house, some 48 kiloms north ofRutlan, we talked about getting wed. I lay back in the seat of my carand through the roof watched the December snow fall—making plans withonly half a mind for moving from my Nork apartment, deciding whetherto keep both cars, arguing whether the commute to Nork took 40 or 45minutes, choosing a sex for the baby. Mostly I was thinking about whatSara had said about the Sun. I'm a Reporter, after all.

When the car locked onto the exit tramway and started deceleration, Isuggested that we go to the Argus office first. Her apartment wasjust upstairs anyway. "We had better," I said, "have a little talk."

The demand sensor of the radiant heater in front of the Argusbuilding was, as usual, out of order, so we didn't linger. Sara pressedher ID bracelet against the night lock and the door swung open with asquawk that lifted my hair.

Once when I asked her why she didn't get it fixed, she said it savedthe price of a cowbell on a spring. I told her then that Vermont hadno business in the 21st century, and she said the 21st century had nobusiness in Vermo