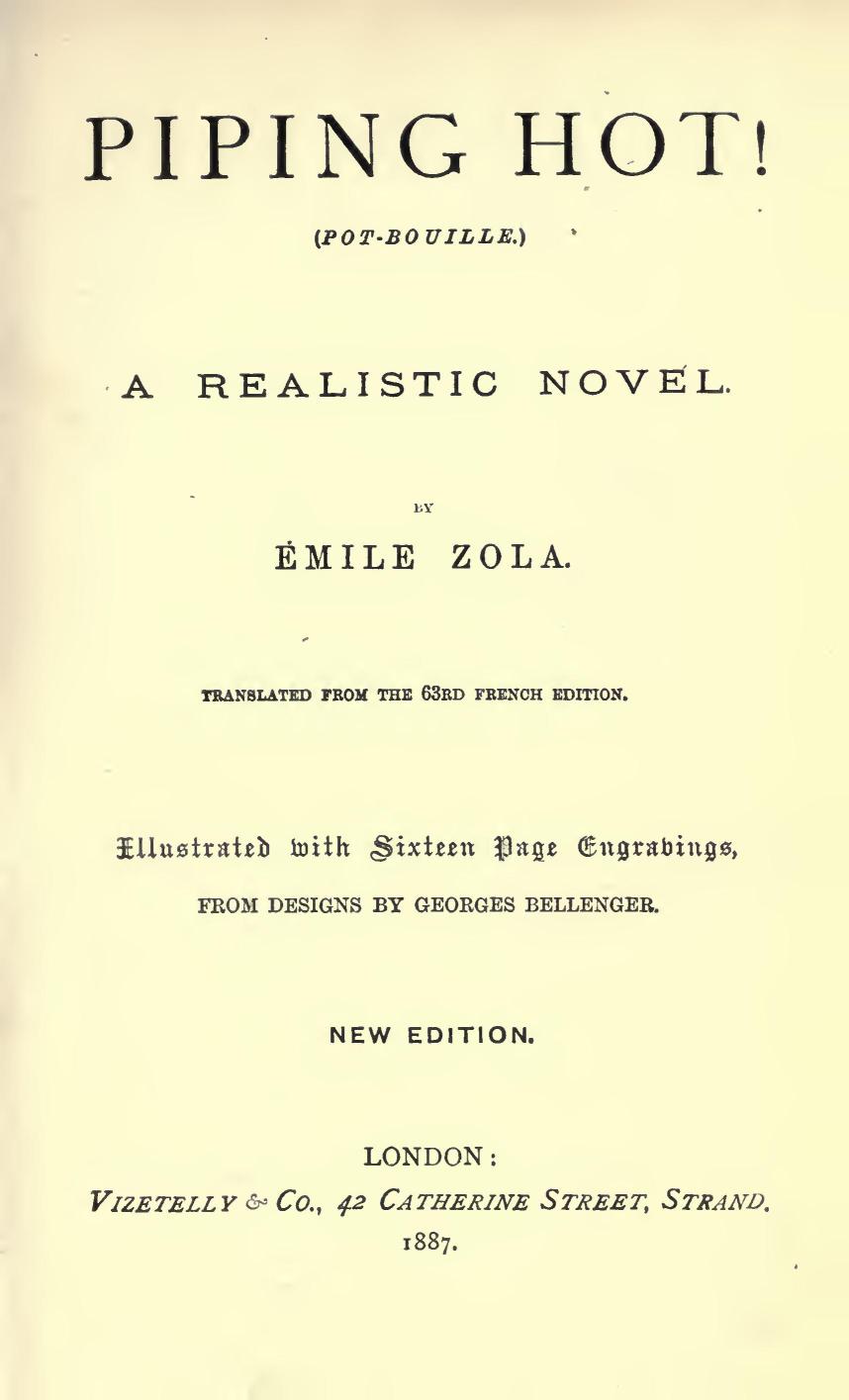

PIPING HOT!

(POT-BOUILLE)

A Realistic Novel

By Émile Zola.

Translated From The 63rd French Edition.

Illustrated With Sixteen Page Engravings

From Designs By Georges Bellenger

London: Vizetelly & Co.

1887.

CONTENTS

PREFACE.

One day, in the middle of a long literary conversation, Théodore Duretsaid to me: “I have known in my life two men of supreme intelligence. Iknew of both before the world knew of either. Never did I doubt, nor wasit possible to doubt, but that they would one day or other gain thehighest distinctions—those men were Léon Gambetta and Émile Zola.”

Of Zola I am able to speak, and I can thoroughly realise how interestingit must have been to have watched him, at that time, when he was poor andunknown, obtaining acceptance of his articles with difficulty, andsurrounded by the feeble and trivial in spirit, who, out of inbornignorance and acquired idiocy, look with ridicule on those who believethat there is still a new word to say, still a new cry to cry.

I did not know Émile Zola in those days, but he must have been then as heis now, and I should find it difficult to understand how any man ofaverage discrimination could speak with him for half-an-hour withoutrecognising that he was one of those mighty monumental intelligences, thestatues of a century, that remain and are gazed upon through the longpages of the world’s history. This, at least, is the impression Émile Zolahas always produced upon me. I have seen him in company, and company of nomean order, and when pitted against his compeers, the contrast has onlymade him appear grander, greater, nobler. The witty, the clever AlphonseDaudet, ever as ready for a supper party as a literary discussion, withall his splendid gifts, can do no more when Zola speaks than shelterhimself behind an e