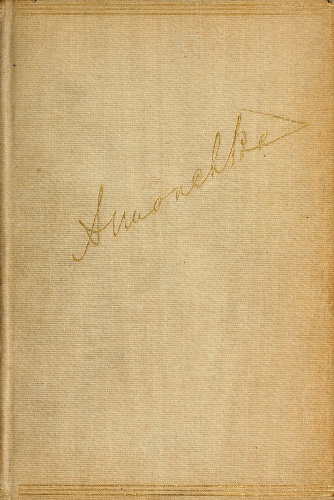

ANNOUCHKA

A Tale

BY IVAN SERGHEÏEVITCH TURGENEF

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH OF THE AUTHOR'S OWN TRANSLATION

BY FRANKLIN ABBOTT

BOSTON

CUPPLES, UPHAM AND COMPANY

1884

Copyright,

By Franklin P. Abbott,

1884.

All Rights Reserved.

C. J. PETERS AND SON,

ELECTROTYPERS AND STEREOTYPERS,

145 High Street.

ANNOUCHKA.

I.

I was then five-and-twenty,—that was a sufficient indication that I hada past, said he, beginning. My own master for some little time, Iresolved to travel,—not to complete my education, as they said at thetime, but to see the world. I was young, light-hearted, in good health,free from every care, with a well-filled purse; I gave no thought to thefuture; I indulged every whim,—in fact, I lived like a flower thatexpands in the sun. The idea that man is but a plant, and that itsflower can only live a short time, had not yet occurred to me. "Youth,"says a Russian proverb, "lives upon gilded gingerbread, which itingenuously takes for bread; then one day even bread fails." But of whatuse are these digressions?

I travelled from place to place, with no definite plan, stopping whereit suited me, moving at once when I felt the need of seeing newfaces,—nothing more.

The men alone interested me; I abhorred remarkable monuments, celebratedcollections, and ciceroni; the Galerie Verte of Dresden almost droveme mad. As to nature, it gave me some very keen impressions, but I didnot care the least in the world for what is commonly called itsbeauties,—mountains, rocks, waterfalls, which strike me withastonishment; I did not care to have nature impose itself upon myadmiration or trouble my mind. In return, I could not live without myfellow-creatures; their talk, their laughter, their movements, were forme objects of prime necessity. I felt superlatively well in the midst ofa crowd; I followed gayly the surging of men, shouting when theyshouted, and observing them attentively whilst they abandoned themselvesto enthusiasm. Yes, the study of men was, indeed, my delight; and yet isstudy the word? I contemplated them, enjoying it with an intensecuriosity.

But again I digress.

So, then, about five-and-twenty years ago I was living in the small townof Z., upon the banks of the Rhine. I sought isolation: a young widow,whose acquaintance I made at a watering-place, had just inflicted uponme a cruel blow. Pretty and intelligent, she coquetted with every one,and with me in particular; then, after some encouragement, she jilted mefor a Bavarian lieutenant with rosy cheeks.

This blow, to tell the truth, was not very serious, but I found itadvisable to give myself up for a time to regrets and solitude, and Iestablished myself at Z.

It was not alone the situation of this small town, at the foot of twolofty mountains, that had impressed me; it had enticed me by its oldwalls, flanked with towers, its venerable lindens, the steep bridge,which crossed its limpid river, and chiefly by its good wine.

After sundown (it was then the month of June), charming little Germangirls, with yellow hair, came down for a walk in its narrow streets,greeting the strangers whom they met with a gracious guten abend. Someof them did not return until the moon had risen from behind the peakedroofs of the old houses, making the little stones with which the streetswere paved scintillate by the clearness of its motionless rays. I lovedthen to