THE

SECRETS OF CHEATING

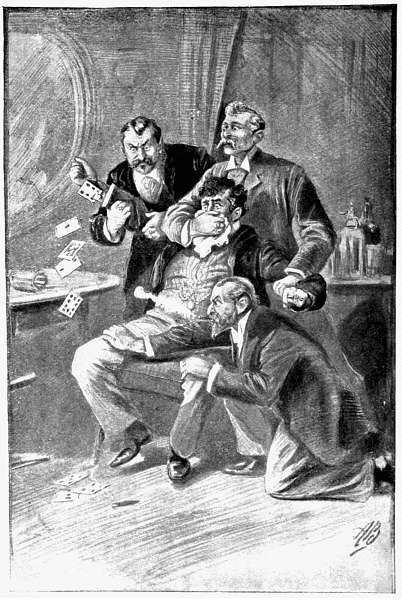

'Then, suddenly and without a moment's warning, Kepplinger was seized, gagged, and held hard and fast.... The great master-cheat was searched, and upon him was discovered the most ingenious holdout ever devised.'—Chap. v. p. 99.

SHARPS AND FLATS

JOHN NEVIL MASKELYNE

1894

THAT MAJORITY SPOKEN OF BY CARLYLE

AND WHICH MAY BE SAID TO INCLUDE

ALL GAMBLERS

THIS BOOK IS PARTICULARLY ADDRESSED

BY THE AUTHOR

PREFACE

In presenting the following pages to the public, I havehad in view a very serious purpose. Here and theremay be found a few words spoken in jest; but throughoutmy aim has been particularly earnest.

This book, in fact, tends to point a moral, and presenta problem. The moral is obvious, the problem isethical; which is, perhaps, only another way of sayingsomething different.

In the realm of Ethics, the two men who exert, probably,the greatest influence upon the mass of humanityare the philosopher and the politician. Yet, strange tosay, there would appear to be little that can be consideredas common knowledge in either politics or philosophy.Every politician and every philosopher holds opinionswhich are diametrically opposed to those of some otherpolitician or philosopher; and there never yet existed,apparently, either politician or philosopher who wouldadmit even that his opponents were acquainted with the[viii]fact of two and two making four. So much, then, fordogmatism.

In the natural order of events, however, there mustbe things which even a politician can understand. Notmany things, perhaps; but still some things. In likemanner, there must be things which even a philosophercan not understand—and a great many things.

As an illustration, let us take the case of 'sharping.'Politician and philosopher alike are interested in theorigin of crime, its development, and the means of its prevention.Now, even a politician can understand that aman, having in view the acquisition of unearned increment,may take to cheating as being a ready means ofpossessing himself of the property of others, with butlittle effort upon his own part. At the same time, I willventure to say that not even a philosopher can renderany adequate reason for the fact that some men will devotean amount of