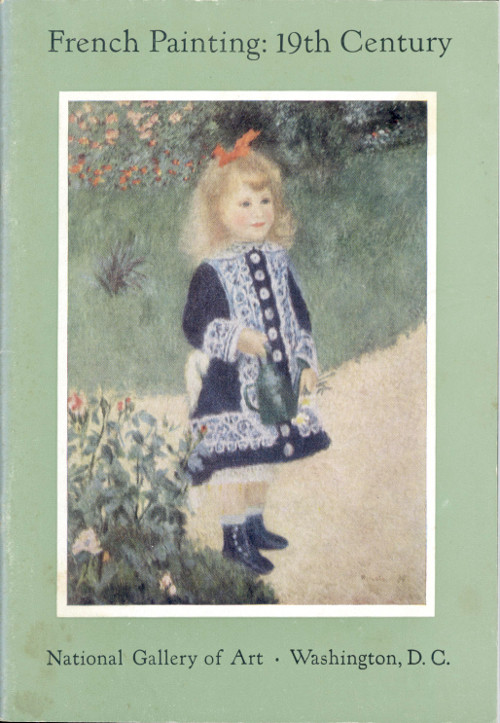

Cover illustration (see description on page 42):

Auguste Renoir (1841-1919)

A Girl with a Watering Can

Canvas. 39½ × 28¾ inches. Dated 1876

Chester Dale Collection

French Painting

of the 19th Century

in the

National Gallery of Art

by

Grose Evans

Curator of Extension Services

Washington, D. C.

Copyright 1959

Publications Fund

National Gallery of Art

Washington, D. C.

Revised 1967

Designed, Engraved, and Printed

in the United States of America by

The Beck Engraving Company

French Painting: 19th Century

The story of French painters during the nineteenthcentury is an exciting one, colored by personal rivalriesand revolutions in taste. In the face of an indifferent orjeering public, artists often had to make great sacrificesto achieve the sincere expression of their ideals. Firmlyestablished academic painters bitterly opposed all youngartists who tried to create new styles, and the inertia ofpopular taste lent such authority to the Academy thatartists could only be original at their own peril.

The academic style grew out of the classical idealismof Jacques-Louis David (page 13). He rose to fame duringthe French Revolution (1789-95) by producing pictureswith propaganda content and attained greatprominence as “the painter of the people.” Son of a Paristradesman, David had been fortunate enough to studypainting in the French Royal Academy. After four failuresand an attempted suicide, he won the Prix de Romeand in 1774 was able to go to Italy, which was thenconsidered the fountainhead of art. There, during a ten-yearstay, he reacted violently against the gay, trivialstyle of painting that French aristocrats had loved. Idolizing2the ancient statues he saw in Rome, he introduceda powerful Neo-Classical style and, after his return toFrance, he reorganized the Academy to sanction only asober and “elevating” imitation of classical art. WhenNapoleon became emperor, in 1804, he appointedDavid his court painter and commissioned a series ofhuge pictures illustrating imperial ceremonies. However,soon after the Bourbon monarchy was restored, in1814, David was exiled to Brussels, where he spent hislast years.

David’s style was continued and refined by his pupilJ.-A.-Dominique Ingres (page 15), whose father was apainter at Montauban. Ingres’ apprenticeship withDavid and eighteen years spent in Italy led Ingres topaint with precise, sculpturesque draftsmanship andcoldly calculated color. To sustain the classical tradition,his subjects were usually drawn from mythology andancient history. After he returned to Paris, in 1824,Ingres’ ideal of perfectionism came to dominate academicart.

Behind it the Academy had the weight of traditionallyaccepted theory and the splendid accomplishmentsof the Old Masters. The theory, growing from ancientclassical concepts of art, seemed infallible and, on sucha theoreti